[ad_1]

One month after I accomplished chemotherapy for Stage 3 breast most cancers, and two weeks after I underwent a double mastectomy, I sat in mattress, my surgical wounds itchy, my morale at an all-time low.

“I’d pay $1,000 if I might have any actual quantity of hair proper now,” I instructed my husband. He nodded, politely understanding, however his eyes widened. We owed a colossal sum on our taxes. I used to be on medical depart from my job. We weren’t precisely flush. However I used to be mendacity: I’d have paid vastly extra than $1,000 to have an actual quantity of hair on my head. I nonetheless would. I’ve performed with totally different theoretical sums: $5,000? Possibly $10,000?

With out hair I really feel diminished, undone. My grief over my hair exceeds, I feel, my grief for my disappeared breasts, or my well being extra typically. There are moments after I fear it is going to swallow me complete, moments when it inches dangerously near despair.

Subsequent to the specter of loss of life—the agency, chilly gun towards your temple that’s most cancers—it appears petty. Shouldn’t I be grateful to have a treatable most cancers, to have accomplished essentially the most onerous parts of therapy? Shouldn’t I be carpe-ing the diem?

I’m not. I’m simply actually unhappy about being bald.

“Your physique is an instrument, not an decoration,” I’ve insisted to the center schoolers to whom I train intercourse ed in my position as a faculty social employee. I’ve tried to arrange them for a world that hopes you’ll at all times wish to look a bit higher than you already do, and to problem the notion that trying good has ethical weight.

However I’m not an fool, nor am I naive: I do know the pull of magnificence. I’ve spent a long time of my life making an attempt to look good. I feel I’ve usually been profitable. Nonetheless, as a girl—even a comparatively assured one—I’m at all times dancing on the sting of acceptability. Not sufficient or an excessive amount of make-up, garments ill-fitting or ill-suited to the event, hair poorly reduce or styled might ship me plummeting off the cliff towards ugliness. In school I by no means went to class in pajamas. If I had a pimple, I lined it with make-up.

Then, a couple of weeks after turning 40, I used to be recognized with breast most cancers. I started chemotherapy, and, like so many most cancers sufferers earlier than me, I confronted the prospect of shedding my hair. I want to inform you that the lesson that I’d tried to impart to my college students rang in my mind, and that I targeted on my well being. That, too, can be a lie.

At first I attempted clinging to the hair. At many hospitals now, chemotherapy sufferers can choose into an costly, considerably questionable world of hair preservation: You freeze your head earlier than, throughout, and after your chemo infusion. “Chilly capping,” as scalp hypothermia is colloquially identified, prices sufferers hundreds of {dollars} (and is mostly not lined by medical insurance). It additionally made me (and I’m not alone) profoundly nauseous, so I needed to be pumped filled with anti-nausea medicine whereas present process chemo. This meant that I used to be, basically, sedated for hours at a time. Whereas having a really chilly head.

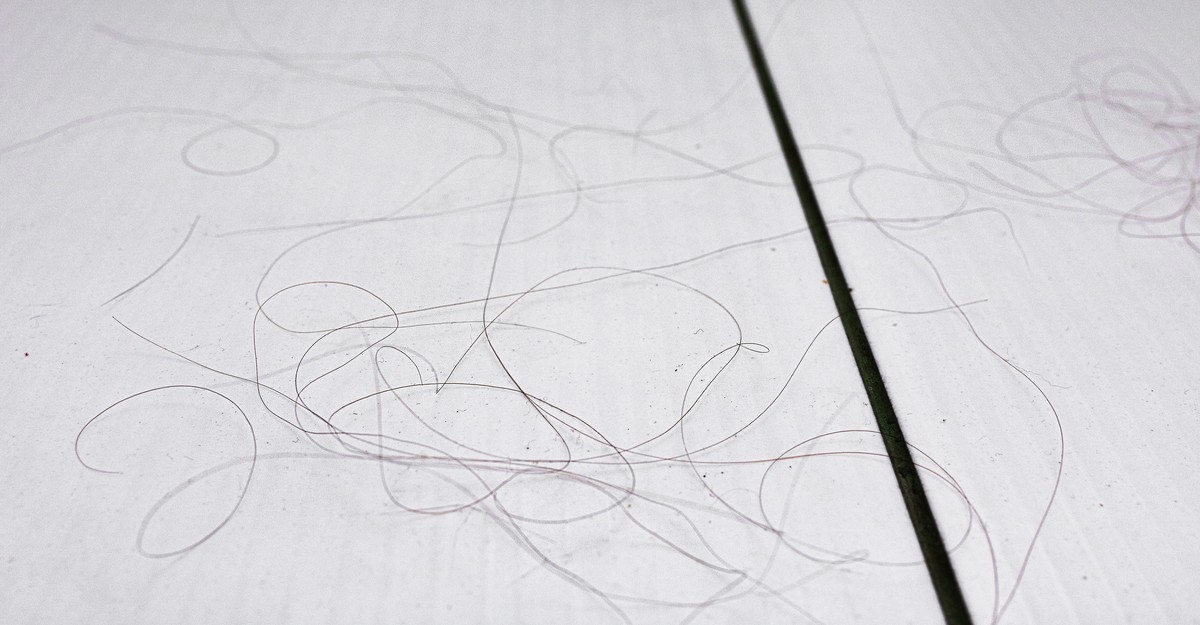

My hair fell out anyway. It fell out in giant clumps. It lined each floor of my bed room and loo. I felt as if I had all of a sudden acquired a loveless Irish setter whom I used to be always cleansing up after however by no means cuddling. I used to be afraid to bathe, as a result of my hair crammed the drain nearly instantly, and the sight crammed me with a rising sense of panic. So my husband, at my request, shaved all of it off.

I used to be not ready for what I noticed within the mirror as soon as my remaining hair was strewn over the toilet flooring. I appeared grotesque.

“I’m a goblin,” I say to my mates. “Like Gollum.” Anyone corrects me: Gollum, from The Lord of the Rings, is a hobbit, not a goblin. However I can’t get his bald, sickly, bug-eyed face out of my thoughts after I look in my toilet mirror.

Pals snort it off, or attempt to speak me down.

“You look stunning,” they inform me.

“You look wonderful. Very punk rock. You actually pull it off.”

I don’t look wonderful. I look hollowed out and alien, and objectively worse than my prior self. However nobody will say this. Nobody will console me, as a result of to console is to confess that there’s a downside.

When my mom died, everybody instructed me how horrible it was to lose such a beautiful mother or father. I felt seen, and supported. Nobody mentioned, “Oh, don’t fear, she’s not really useless.” If that they had, I’d have cried tougher.

I acknowledge that I’ve been a part of this charade, with my false cheer about devices and ornaments, my lesson plans. I really feel determined for somebody to agree that trying worse feels very dangerous, however I’m additionally determined for this nonsense—the idea that we’re all equally stunning, or that being decorative is unimportant—to be true. Harder than residing in an appearance-obsessed tradition resides in an appearance-obsessed tradition that pretends that look doesn’t matter, or pretends that everybody is equally visually acceptable.

To call my agony, I need to admit that I as soon as felt fairly, which sounds useless or prideful. The socially acceptable approach to speak about your self is a tightrope. It will even be uncouth to explain myself as feeling perpetually ugly. I’d be fishing for compliments, or demonstrating depressingly low vanity. However to inform you that for years I admired my reflection? If I’m going to admit this, absolutely I had higher wrap these phrases in a comeuppance, or a lesson about how magnificence doesn’t matter. I scramble round for an ethical, hoping to seek out one however developing empty. Shedding my hair and feeling ugly on this panorama has not improved my character, or supplied me with a brand new perspective on life. It has simply made me depressed.

“It’s going to develop again,” folks remind me, as if I didn’t know that.

“It’s short-term!”

They’re proper. So how, then, do I make sense of the emotions of horror and disgrace which have shrouded me since my husband shaved my head, my kids huddled outdoors the door: unwilling to observe however riveted by this scary transformation?

I pester different ladies who’ve undergone chemo about how they felt about shedding their hair. They’re uniform, each of their unhappiness and of their eagerness to inform me about their distress. They virtually leap towards me of their pleasure to reply my query. I hated it, they report. I felt like a monster, one mentioned. It was a trauma. I deleted each image on my telephone from that point. If I’m carrying a hat that covers my hair and I catch sight of my reflection, I start to panic. A 2019 research discovered that almost 60 % of the 179 most cancers sufferers surveyed skilled hair loss because the worst aspect impact of chemotherapy. These persons are dealing with loss of life. Chemo makes you’re feeling very sick. However what’s even worse than nausea, or crippling fatigue, or explosive diarrhea? Trying like a goblin. Or feeling as if you do.

“All our bodies are good our bodies,” I’d write on the whiteboard for the 12-year olds. “Let’s speak about this,” I mentioned brightly. I defined about ableism, and fatphobia, and the racism of magnificence requirements. A few of them nodded alongside, earnest and able to purchase what I used to be promoting. A few of them smelled bullshit, wrinkling their noses. What did they make of me, with my lengthy hair and skinny body, my blue eyes and denims that match properly, and my subtly lipsticked mouth? I don’t know. However I ponder: When my tsunami of physician appointments and coverings has receded and I return to work, will I say this to them once more? This was as soon as a theoretical place, and it was simple for me to consider in it. However now my physique has tried to homicide me, and what’s extra, I hate the way in which it seems to be.

I wrestle with this as I’m going about my day-to-day life. I’ve no actual proof that anybody treats me in a different way from earlier than, though a baby at my kids’s college misgenders me, a lot to my daughter’s horror. (I’m embarrassed, however unsurprised.) However in every single place I’m going, the absence of my hair haunts me. I really feel like explaining to the barista on the espresso store: I used to have hair, and eyelashes and eyebrows. I used to look higher.

I really feel sure—extra sure than I’ve ever felt of something—that when my hair does return, masking my pink-white scalp and the brow that I’ve at all times thought was too giant, I will be comfortable once more.

It’s the most cancers, you could be pondering. Not the hair. It’s the sickness, the fixed drain of excited about your personal mortality. It’s the worry, the nervousness, the melancholy that accompanies a Very Critical Illness. And naturally it most likely is, to some extent. However I invite you to think about the likelihood that quite a lot of it’s the hair.

After I was recognized at 40, I used to be on my method down the staircase of center age, already descending into invisibility. However this enterprise of being bald, this is like slipping while you’re midway down the steps, falling with painful and terrifying velocity. And now I can’t wait to return to that gradual state of decline.

Will that be the present of most cancers: to pressure me into gratitude for my graying hair, my marionette traces? I can’t inform you but. However I think about returning to work, talking loudly from the entrance of the room. “Trying good typically feels actually good,” I’ll inform the center schoolers. “All of us prefer to faux that it doesn’t matter. However feeling such as you look dangerous stinks.”

In the center of my summer time of chemotherapy, on a uncommon evening after I was feeling energetic, my husband and my kids and I met my sister’s household on the seaside for dinner. The solar was setting, so I used to be not carrying a hat as we corraled ourselves and our sandy belongings into the automobile afterward. A lady stopped me within the car parking zone. “Chemo?” she requested. I nodded. She instructed me that she had been cancer-free for a couple of years. “Take a look at my hair!” she implored me. It was nothing particular—lengthy, messy and beachy, graying—and but it was, as a result of it was there. I discovered myself crying. She requested if she might give me a hug, and I accepted, and allowed her to fold her arms round me, and felt her hair towards my bathing swimsuit.

She had noticed me: I caught out like a sore thumb, and she or he didn’t faux in any other case. She acknowledged, out loud, that I appeared and felt unusual. I considered her each few days for the rest of my therapy, and the way comforted I’d felt by this stranger seeing me, calling out, and holding me in her arms.

[ad_2]